Anti-inflammatory Activity of Water Extract of Luvunga sarmentosa (BI.) Kurz Stem in the Animal Models

Abstract

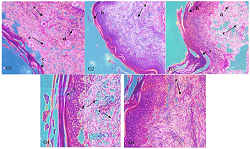

The study was aimed to determine the anti-inflammatory activity of water extract of the Luvunga sarmentosa stem in an animal model. Twenty-five Wistar rats were divided into five groups (n=5). Group 1 was administered 0.9% normal saline (negative control), group 2 was administered 150 mg/kg diclofenac sodium (positive control), and groups 3 to 5 were administered 50, 300, and 550 mg/kg BW of L. sarmentosa extract, respectively. Carrageenan was injected subcutaneously into each rat's subplantar region of the left hind paw. The paw volume was measured using a plethysmometer. The results showed that the water extract of L. sarmentosa stem (doses of 50, 300, and 550 mg/kg BW) significantly reduced the paw edema volume from the 4th to 5th hour compared to the negative control. The percent inhibition of edema at the 5th hour is 47.45; 46.95; 50.39%. The first phase of the edema (1st and 2nd hour) was not affected by the extract. Meanwhile, diclofenac sodium decreased paw edema volume from the 1st to 5th hour with a percent inhibition of 95.90% at the 5th hour. The histopathology result is relevant to the percentage inhibition of edema. Treatment with L. sarmentosa extract showed slight improvement, destruction of epidermal tissue, hyperkeratotic skin, and subepidermal edema. Meanwhile, positive control showed no inflammatory signs with normal keratin, subepidermal, and subcutaneous layers. The water extract of L. sarmentosa stem has anti-inflammatory activity. This extract effectively reduces the paw edema volume in the late phase with decreased neutrophil infiltration.

Full text article

References

2. Jargalsaikhan BE, Ganbaatar N, Urtnasan M, Uranbileg N, Begzsuren D. Anti-Inflammatory effect of polyherbal formulation (PHF) on carrageenan and lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation in rats. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2019;12(4):1801–9. doi:10.13005/bpj/1811

3. Walter EJ, Hanna-Jumma S, Carraretto M, Forni L. The pathophysiological basis and consequences of fever. Crit Care. 2016;20:200. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1375-5

4. Abdulkhaleq LA, Assi MA, Abdullah R, Zamri-Saad M, Taufiq-Yap YH, Hezmee MNM. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet World. 2018;11(5):627-35. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2018.627-635

5. Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. 2019;25(12):1822-32. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0

6. Bennett JM, Reeves G, Billman GE, Sturmberg JP. Inflammation-Nature's Way to Efficiently Respond to All Types of Challenges: Implications for Understanding and Managing "the Epidemic" of Chronic Diseases. Front Med. 2018;5:316. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00316

7. DiSabato DJ, Quan N, Godbout JP. Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 2):136-53. doi:10.1111/jnc.13607

8. Bindu S, Mazumder S, Bandyopadhyay U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;180:114147. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114147

9. Wongrakpanich S, Wongrakpanich A, Melhado K, Rangaswami J. A Comprehensive Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in The Elderly. Aging Dis. 2018;9(1):143-50. doi:10.14336/ad.2017.0306

10. Drini M. Peptic ulcer disease and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aust Prescr. 2017;40(3):91-3. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2017.037

11. Tungmunnithum D, Thongboonyou A, Pholboon A, Yangsabai A. Flavonoids and Other Phenolic Compounds from Medicinal Plants for Pharmaceutical and Medical Aspects: An Overview. Medicines. 2018;5(3):93. doi:10.3390/medicines5030093

12. Oyebode O, Kandala NB, Chilton PJ, Lilford RJ. Use of traditional medicine in middle-income countries: a WHO-SAGE study. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(8):984-91. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw022

13. Zulkipli IN, David SR, Rajabalaya R, Idris A. Medicinal Plants: A Potential Source of Compounds for Targeting Cell Division. Drug Target Insights. 2015;9:9-19. doi:10.4137/dti.s24946

14. Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4:177. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00177

15. Salmerón-Manzano E, Garrido-Cardenas JA, Manzano-Agugliaro F. Worldwide Research Trends on Medicinal Plants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3376. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103376

16. Wardah, Sundari S. Ethnobotany study of Dayak society medicinal plants utilization in Uut Murung District, Murung Raya Regency, Central Kalimantan. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2019;298(1):012005. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/298/1/012005

17. Fauzi F, Widodo H. Short Communication: Aphrodisiac plants used by Dayak Ethnic in Central Kalimantan Province, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2019;20(7):1859-65. doi:10.13057/biodiv/d200710

18. Wati H, Muthia R, Jumaryatno P, Hayati F, August J. Phytochemical screening and aphrodisiac activity of Luvunga Sarmentosa (Bi.) Kurz ethanol extract in male wistar albino rats. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2018;9(931):931–7.

19. Lien TP, Kamperdick C, Schmidt J, Adam G, Van Sung T. Apotirucallane triterpenoids from Luvunga sarmentosa (Rutaceae). Phytochemistry. 2002;60(7):747–54. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00156-5

20. Han YM, Woo S-U, Choi MS, Park YN, Kim SH, Yim H, et al. Antiinflammatory and analgesic effects of Eurycoma longifolia extracts. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39(3):421–8. doi:10.1007/s12272-016-0711-2

21. Haddadi R, Rashtiani R. Anti-inflammatory and anti-hyperalgesic effects of milnacipran in inflamed rats: involvement of myeloperoxidase activity, cytokines and oxidative/nitrosative stress. Inflammopharmacology. 2020;28(4):903–13. doi:10.1007/s10787-020-00726-2

22. Rajput MA, Zehra T, Ali F, Kumar G. Evaluation of Antiinflammatory Activity of Ethanol Extract of Nelumbo nucifera Fruit. Turkish J Pharm Sci. 2021;18(1):56–60. doi:10.4274/tjps.galenos.2019.47108

23. Tatiya AU, Saluja AK, Kalaskar MG, Surana SJ, Patil PH. Evaluation of analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of Bridelia retusa (Spreng) bark. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;7(4):441-51. doi:10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.12.009

24. Patil KR, Mahajan UB, Unger BS, Goyal SN, Belemkar S, Surana SJ, et al. Animal Models of Inflammation for Screening of Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Implications for the Discovery and Development of Phytopharmaceuticals. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4367. doi:10.3390/ijms20184367

25. Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenin-induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiinflammatory drugs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–7. doi:10.3181/00379727-111-27849

26. Mansouri MT, Hemmati AA, Naghizadeh B, Mard SA, Rezaie A, Ghorbanzadeh B. A study of the mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of ellagic acid in carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47(3):292–8. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.157127

Authors

Copyright (c) 2022 Sabar Deyulita, Hilkatul Ilmi, Hanifah Khairun Nisa, Lidya Tumewu, Aty Widyawaruyanti, Achmad Fuad Hafid

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Authors continue to retain the copyright to the article if the article is published in the Borneo Journal of Pharmacy. They will also retain the publishing rights to the article without any restrictions.

Authors who publish in this journal agree to the following terms:

- Any article on the copyright is retained by the author(s).

- The author grants the journal the right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share work with an acknowledgment of the work authors and initial publications in this journal.

- Authors can enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of published articles (e.g., post-institutional repository) or publish them in a book, with acknowledgment of their initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their websites) prior to and during the submission process. This can lead to productive exchanges and earlier and greater citations of published work.

- The article and any associated published material are distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.